Being a pioneer was not easy for Perry Wallace and only in the last five years of his life did he begin to see and understand the appreciation for what he had done in his lifetime. Wallace was the first African-American basketball player in the Southeastern Conference, and his life was the focus of a presentation by author Andrew Maraniss Feb. 27 at Samford University.

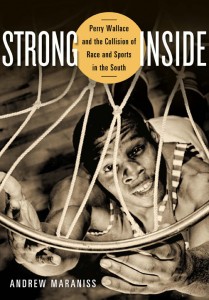

Maraniss, who wrote about Wallace in the book, Strong Inside, spoke as part of the university’s 50th anniversary commemoration of integration.

Wallace, who died in December, was a high school basketball star in Nashville before he was recruited to play basketball at Vanderbilt University. While being recruited by schools in the North and Midwest, Wallace saw the “ugly side of college sports,” Maraniss said.

“He decided he wasn’t going to leave the South, where he wasn’t respected as an equal person, to go to a school where he would be exploited for his athletic ability,” he added. “He knew it would be difficult to be a pioneer, but he knew he would receive a good education at Vanderbilt.”

Maraniss told the Samford audience that he considered Wallace a hero for what he did.

“A hero is a person who by their words and deeds makes the world a better place,” Maraniss explained. “Perry Wallace became known, not for his blocked shots and baskets made, but for everything else that he did.”

During high school in the mid-1960s, Wallace felt that things were changing in the country, and there might be opportunities for him that hadn’t existed for his older siblings. He was prepared, both as a student and a basketball player. He was valedictorian of his graduating class at Nashville’s Pearl-Cohn High School and played on three state championship teams.

What he was not prepared for, though, was the loneliness that he felt as a Vanderbilt student. No one would sit beside him in class or the cafeteria. There were no fraternities or sororities on campus to serve its African American students.

Ultimately, the most courageous thing that Wallace did was to “tell the truth” about his experiences as he was graduating. Some praised his honesty, while others criticized him for what they saw as “sour grapes” after receiving the educational opportunity that he did.

“In the interview he talked about how difficult things had been for him,” Maraniss said. “He felt that he had a moral obligation to the students who would come after him, so the university would know the truth. He was afraid that no one would listen.”

After receiving his degree, Wallace earned a degree from Columbia University’s law school and eventually became a faculty member at American University in Washington, D.C. But, he was not invited back to the Vanderbilt campus for 20 years. Eventually, the university reached out to him through Vanderbilt’s then-head coach C. M. Newton, who had been the basketball coach at the University of Alabama when Wallace was playing for Vanderbilt. Vanderbilt now presents the annual Perry Wallace Courage Award.

Maraniss praised Newton, who is the father of Samford Athletics Director Martin Newton, as one who “did the most to transform life for African American student athletes in the south.” He was head coach or an athletics administrator at four universities, including Vanderbilt.

Maraniss encouraged the Samford audience to think about how they wanted to be remembered in life.

“Perry was surrounded by a lot of bystanders at Vanderbilt,” he explained, “who realized later that they had a classmate and teammate who was being treated unfairly, but they didn’t do anything about it.

“Do you want to be remembered as bystander or an ‘upstander’? Think about that in your everyday life.”

Having Maraniss on campus was a special opportunity as part of Samford’s anniversary commemoration, according to Denise Gregory, Samford’s assistant provost for diversity and intercultural initiatives.

“Andrew, through his telling of Perry Wallace’s story, was able to provide us with context of how a pioneer African American student helped change the culture at a major university in much the same way that Samford’s pioneer Audrey Gaston Howard did,” Gregory said. In 1967, Howard was the first African American student to enroll at Samford.